I recently submitted a paper on artificial intelligence, carbon markets and sustainability governance in the European Union, where I repeatedly return to a structural problem that goes far beyond climate policy and moves to the heart of the current debates about European teach sovereignty. Public goods are increasingly governed through private digital infrastructures. This is not a marginal technical issue. It is a constitutional one.

Debates on digital sovereignty often focus on platforms, clouds or communications tools. The deeper issue sits one layer below, in the infrastructures of verification, trust and coordination that now underpin core public functions, from justice and public administration to climate governance and sustainability reporting. When these infrastructures are privately designed, operated and controlled, the state does not merely outsource services, but it delegates power.

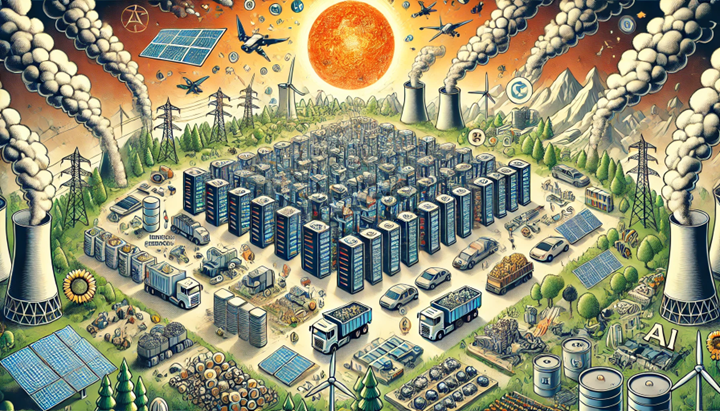

This is particularly visible in carbon markets and sustainability reporting, where systems of measurement, reporting and verification have become the backbone of regulatory effectiveness. Emissions are no longer governed primarily through inspections or permits, but through data pipelines. Sensors, platforms, algorithms, standards and registries translate physical reality into data, data into compliance and compliance into legal and economic consequences. Whoever controls that translation layer exercises a form of functional sovereignty.

Private digital infrastructures are often presented as neutral, efficient and scalable. In practice, they embed choices about methodologies, thresholds, defaults and visibility. In carbon markets, this means deciding what counts as a real reduction, how uncertainty is treated, how anomalies are detected and which data are considered authoritative. These are not technical details. They are normative decisions with distributive effects.

The problem is not the involvement of private actors. European regulation has long relied on hybrid governance. The problem is that the architecture itself is frequently opaque, fragmented and weakly accountable. In sustainability governance, this has translated into inconsistent MRV standards, low quality carbon credits, greenwashing risks and a widening gap between regulatory ambition and implementation capacity. Similar patterns appear whenever public objectives depend on proprietary systems governed by foreign legal orders or commercial incentives.

Recent European moves away from non European digital services in the public sector are often framed as geopolitical reactions, but they are also responses to a rule of law risk. When public institutions rely on infrastructures they do not control, continuity of service, data integrity and institutional autonomy become contingent.

This risk is particularly acute in sustainability governance. Climate policy is cumulative and long term. It depends on historical data, methodological consistency and institutional memory. Vendor lock in, opaque algorithms or sudden changes in service conditions can undermine not only efficiency but also legal certainty and democratic legitimacy. A carbon market that cannot credibly verify emissions is not merely inefficient. It is normatively hollow.

What follows from this is not technological isolationism. The European response, increasingly visible in policy, is more structural. Certain digital systems must be treated as regulatory public goods. This includes MRV infrastructures, digital identity, trust services, registries and core data spaces. The objective is not that the state builds everything itself, but that the rules of the system, its interoperability, auditability and ultimate control remain public., and for that there should be certainty that they are subject to European law.

This is where the European digital rulebook matters. Instruments such as data protection law, the artificial intelligence framework, digital identity rules and cybersecurity obligations are often criticised as burdens, although their deeper function is infrastructural. They aim to ensure that innovation occurs within an environment where public values such as rights, accountability and proportionality are not external constraints but design parameters.

In the sustainability domain, this logic is already visible in the gradual move away from purely private carbon standards toward European level certification, registries and verification rules, and the lesson generalises for other tech domains. If the objective is public, the infrastructure cannot be entirely private.

The real risk for Europe is not that it regulates too much, but that it confuses speed with progress. Innovation built on fragile and unaccountable infrastructures ultimately erodes trust, and trust is itself an economic and political asset. By insisting that core digital infrastructures serving public purposes remain governed as such, Europe is not rejecting innovation. It is redefining its conditions, and contradictorily making it more pro innovation by giving legal certainty, which the ill conceived onmibus package is eroding.

Digital sovereignty, understood this way, is not about borders in cyberspace. It is about ensuring that when public goods run on code, that code is embedded in a legal and institutional architecture compatible with European constitutional principles. This approach is slower and more demanding, but it is substantially more resilient, and in a world where governance increasingly happens through systems rather than statutes, resilience may be Europe’s most underestimated innovation strategy.