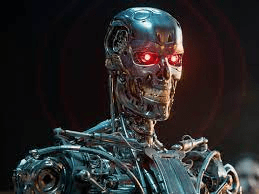

There was a time when we imagined that the end of times would be marred with steel robots crushing the humans that tried to disconnect them, or enslaved them as a source of energy, but while science fiction has provided plenty of accurate predictions of things to come, it seems that end of the society as we know it may come from something less muscular and more subtle. We are going through days when it is almost impossible to open any social media site or publication without bumping into a discussion about the uses, benefits and problems from the use of freely available Natural Language Processing algorithmic systems that seem to create texts of almost anything better than humans.

Leaving aside that it is actually not true that the available systems create text better than humans, as they are quite basic, rigid and plagued of errors, let’s assume for a moment that they are indeed better than humans in creating those texts. There is a pervasive mistake making the algorithm the centre of the discussion, and the hero of the imagined saving-all AI. As many know and have pointed out, the centre, the middle and the periphery of everything that AI can do is the DATA (yes, with capital letters!). There are plenty of writing about the ownership and privacy of such a data and, therefore, the resulting text (or image), but the crucial issue, the one with the capability of creating judgment-day scenario, is the quality of the data.

There is some true in the statements that AI is not biased per se, but there is even more true in the fact that by using biased data AI can replicate and reinforce the original bias, so much that it can convert it in the new, accepted as unbiased, reality. The same applies to any form of AI, including descriptive, predictive and prescriptive, where the description, the prediction and the prescription is based on data that is biased, or incomplete, or plainly wrong, or a combination of all or any of those.

Let’s use as example Facebook and the way that it shows users news in the feed and advertising. There are many “studies” that say that with XX number of “likes” Facebook knows what are your preferences and with a YY number of them it can predict better than yourself what you like and want, but that is not entirely true. It is more accurate to say that, based on what you actually like, Facebook shows you news and adds that are close to it but usually with a tendency to move towards what the advertiser wants you to like, in such a subtle manner that YY likes later you are actually liking what Facebook or the advertiser wanted you to like in the first place. Do you really think that millions of Americans woke up one day and just for their dislike of Hillary decided to vote for a misogynistic, fraudster, liar and megalomaniac like Trump? If you believe that you are not getting the gravity of the Cambridge Analytica scandal and how by knowing the actual preferences of people, an algorithm can start crawling-pegging their interest until they are somehow remote and even the opposite of what they originally wanted (yes, some of those who originally were sincerely abhorred by the idea of a sitting US president having an affair with an intern and then lying under oath, were the same who then supported a women-grabbing, “friend” of a paedophile, who knowingly tried to subvert the basis of their democracy).

Now let’s imagine that it is not “friends” news or adds what the algorithm is showing you, but your whole consumption of news, data, science and information, which is written specially for you; that every time you want to know something you have a system that does not give you a link to a page but gives you a text saying what actually “is” (in the ontological sense). Although it sounds great and the possibilities seem endless, yes you guessed, it all depends on the quality of the data to which the system has access to. Currently most AI systems are “fed” data to train them so they know how to behave in certain situations, even in a biased form, but the ultimate goal is to unleash them in the wealth of data constituted by Internet, mainly because there is where the money is. As you are already guessing, here is where we have the judgement day moment may arise, that moment when Skynet is connected to Internet and the machines kill everyone around them. No killing here, but the effects can be also daunting.

If social media and its algorithmic exacerbation of unethical and unprofessional press has led to massive manipulation, making people choosing social self-harm at the levels we’ve seen in Brexit, Trump, Bolsonaro, different forms of Chavism and a long list of people choosing what will damage them and their community, only imagine if all information they receive, everything that they “write” or ask the system to write come from this data-tainted algorithmic description, prediction and prescription. A different, soon coming, post is needed to the issue of data quality and the role of the established press in the misinformation campaings, but it is clear that we need to start discussing that, besides how bad AI chats are supposed to be for essays as form of assessment, there is a prospect of real social dissolution by misinformation and manipulation at scale not seeing until now.