1 October 2027

The world stirred into a morning not unlike any other. Markets opened in Asia with a gentle hum of anticipation, commuters in Tokyo and Seoul spilled into subway cars, and diplomats in Brussels prepared their agendas for the EU’s routine morning briefings. But for a few sharp eyed analysts buried deep in think tanks and defence outposts, the data looked…wrong. And then, at 08:03 Beijing Standard Time, the first open source satellite images hit the public domain, posted by an amateur tracker on a Taiwanese message board. The post was titled simply: “Looks like they’re moving.”

It was more than movement. At first glance, it was subtle, a fleet of Type 055 destroyers departing the naval base in Qingdao, formation tight, heading southeast. But the next image was unmistakable: satellite photographs from an American commercial provider showed DF-21D missile launchers repositioning in Fujian Province, nose cones unmistakably trained toward the Taiwan Strait. Then, the PLA’s Southern Theatre Command issued an uncharacteristically aggressive communique, cryptic and ominous: “We are prepared to enforce the sovereignty of the Chinese people.”

By 09:15 CST, state run Xinhua had dropped the veil: China was initiating “Joint Sword 27,” a comprehensive set of “strategic exercises” encircling Taiwan. The name, oddly poetic for something so brutal. No warning, no gradual buildup. Just precision and shock. Jets screamed over the Bashi Channel, PLAAF J-20 fighters executing sharp turnarounds along Taiwan’s southern air defence identification zone. Dozens of PLAN warships were picked up fanning out in tight arcs between Hainan and the east coast of Taiwan. Submarine activity, especially from the Type 093 Shang-class nuclear-powered attack subs, spiked dramatically. Chinese fishing vessels, long suspected of dual use, formed thick, erratic swarms around Taiwan’s offshore islands.

In Taipei, sirens didn’t blare. The government knew better. It wasn’t war, not yet, but it was something worse than peace. Premier Lin Yicheng addressed the nation with calm and martial precision, standing before the blue-and-white flag. “We will not react with haste. We will not blink.” But as his address aired, Tainan’s coastal radar stations were already registering electromagnetic interference, the kind that suggested cyber operations, jamming, maybe even the deployment of high-altitude balloons or low-orbit drone constellations. Taiwan’s command centres went dark for thirty four minutes. Not offline, just quiet. Waiting.

In Washington, the day had barely begun when the President was briefed. By 02:45 EST, the day visit to the golf course had been suspended and the Air Force One had been readied for immediate contingency operations. The Secretary of Defence convened with the Joint Chiefs, and analysts at the Pentagon watched, with grim familiarity, the initial contours of an invasion play out in grainy real-time.

As the sun dipped below the South China Sea, and the silhouettes of Chinese amphibious assault ships loomed closer to the Pescadores, the world held its breath. For the first time in generations, war felt less like a relic and more like a schedule.

And someone, somewhere, had kept the time perfectly.

Section Two: Capitals on the Edge

However, the first reaction came not from Washington, Tokyo, or Brussels, but from New Delhi.

India, always wary of Beijing’s intentions, had spent the last five years deepening ties with the West and cautiously modernizing its military. By 1 October, 17:40 IST, the Indian Prime Minister had convened a National Security Council emergency session at South Block. Satellite imagery of Chinese naval movement across the South China Sea was projected onto a wall once adorned only with diplomatic flags. Inside the room, no one used the word “war.” But they all knew the script. For India, the implication was immediate: if the Taiwan situation escalated, the northern Himalayan border could again become a flashpoint. Troop deployments to Ladakh were quietly doubled. The Andaman and Nicobar Command, India’s easternmost tri-service outpost, shifted to readiness condition “Tango Red.” Radar stations along the Bay of Bengal watched the skies like never before.

In Tokyo, silence was louder than any alarm. The Japanese government had been caught in a dilemma it had long feared: the US needed its bases, its backing, and its moral authority, but any visible Japanese involvement risked enraging Beijing and inviting strikes within minutes. Furthermore, after the US initiated trade wars, Tokyo had grown closer to Beijing and Seoul, at expense of Washington. At Yokota Air Base, American F-35s sat in sleek silence, pilots on standby. Japanese destroyers, including the Izumo-class helicopter carriers, began repositioning from Sasebo and Kure, their courses concealed under “joint maritime training protocols.” But Prime Minister Fujimoto knew the line he walked was razor-thin. Japan released a carefully worded statement: “We are monitoring the situation with deep concern and are committed to regional stability in cooperation with our partners.” Internally, Tokyo knew that “monitoring” was code for counting missiles and measuring time in seconds.

In Brussels, the European Union was caught flat footed, as always. The early hours of 1 October had seen some murmurs in foreign affairs circles, but the official agenda for the day remained unchanged until well past midday. The rotating presidency scrambled to call an emergency meeting of the Foreign Affairs Council. France pushed for measured diplomacy. Poland demanded outright condemnation of China. Germany, wary of economic retaliation, stayed cagey, its automotive giants too entangled with the Chinese market to speak clearly.

At the Élysée Palace, the French President met behind closed doors with military advisers and economic ministers. “They’re not bluffing,” his intelligence chief said flatly. France ordered the Charles de Gaulle carrier to remain near Djibouti rather than head to the Indo-Pacific as planned. The world’s powers were hedging, shifting, recalculating. Not yet choosing sides, but drawing breath.

London, meanwhile, found itself in a familiar and unwanted position: a supporting actor in someone else’s crisis. Yet the stakes were real. The City started to absorb some of the shockwaves sent by the Chinese moves, with the pound sliding by nearly 2% before stabilizing. At 10 Downing Street, the Prime Minister met with MI6, the Treasury, and representatives of the Bank of England. Publicly, the UK called for “respect for international law.” Privately, the conversation was far more cynical. “The Chinese don’t seem to be playing games, and we need to be ready to act”.

In Moscow, the Kremlin had long predicted this day, and planned for it. President Putin, still ironclad in power despite growing internal rumblings and the Ukrainian retreat, appeared on state television that evening to express Russia’s “understanding” of China’s actions. “We have always respected the internal matters of sovereign nations,” he said with a slow, deliberate smirk. Russian diplomats began subtly pushing a narrative across international media: this wasn’t aggression, this was the end of Western hegemony in the region. For Moscow, it was more than spin. It was opportunity. In the past few years Russian gas exports to China spiked as new contracts were signed in yuan, not dollars, so supporting China was not without a view on economic gains.

In Tel Aviv, Riyadh, Ankara, and Cairo, the reactions were fragmented and self-interested. Regional power players saw the tremors but waited for aftershocks. Oil prices surged past $140 a barrel, briefly touching $150 before OPEC stabilized the futures with vague promises of increased production. But the mood in Middle Eastern capitals was clear: China decided that the end of the old world order, bulldozed by the US in recent years, implied a free reign to accommodate the region at its will.

And in Washington, the heart of the storm, the White House had become a fortress. Behind the thick walls of the Situation Room, the President sat with the Secretary of State, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, and the Treasury Secretary. Every screen showed a different theatre: troop movements near the Taiwan Strait, economic indicators flashing crimson, cyber threat assessments. The National Security Advisor spoke in clipped, practiced tones. “The consequences of their movements are in every front, military, economics, cyber. They’ve impacted the whole chessboard.”

The President, grave and weary, nodded slowly. “And what’s the board telling us now?”

A long silence.

“The massive moves, not yet an invasion, seems designed not to win,” the Treasury Secretary finally said, “but to end the game.”

Outside the White House, protestors had already begun gathering. On Wall Street, pension funds were staring to what had become usual since the trade wars, down brutal numbers. And in a quiet cyber facility in Maryland, an NSA analyst found an anomalous data packet originating from a Chinese server farm. It had penetrated a civilian water utility in California, not with malware, but with something worse: silence. It wasn’t a bug. It was a test.

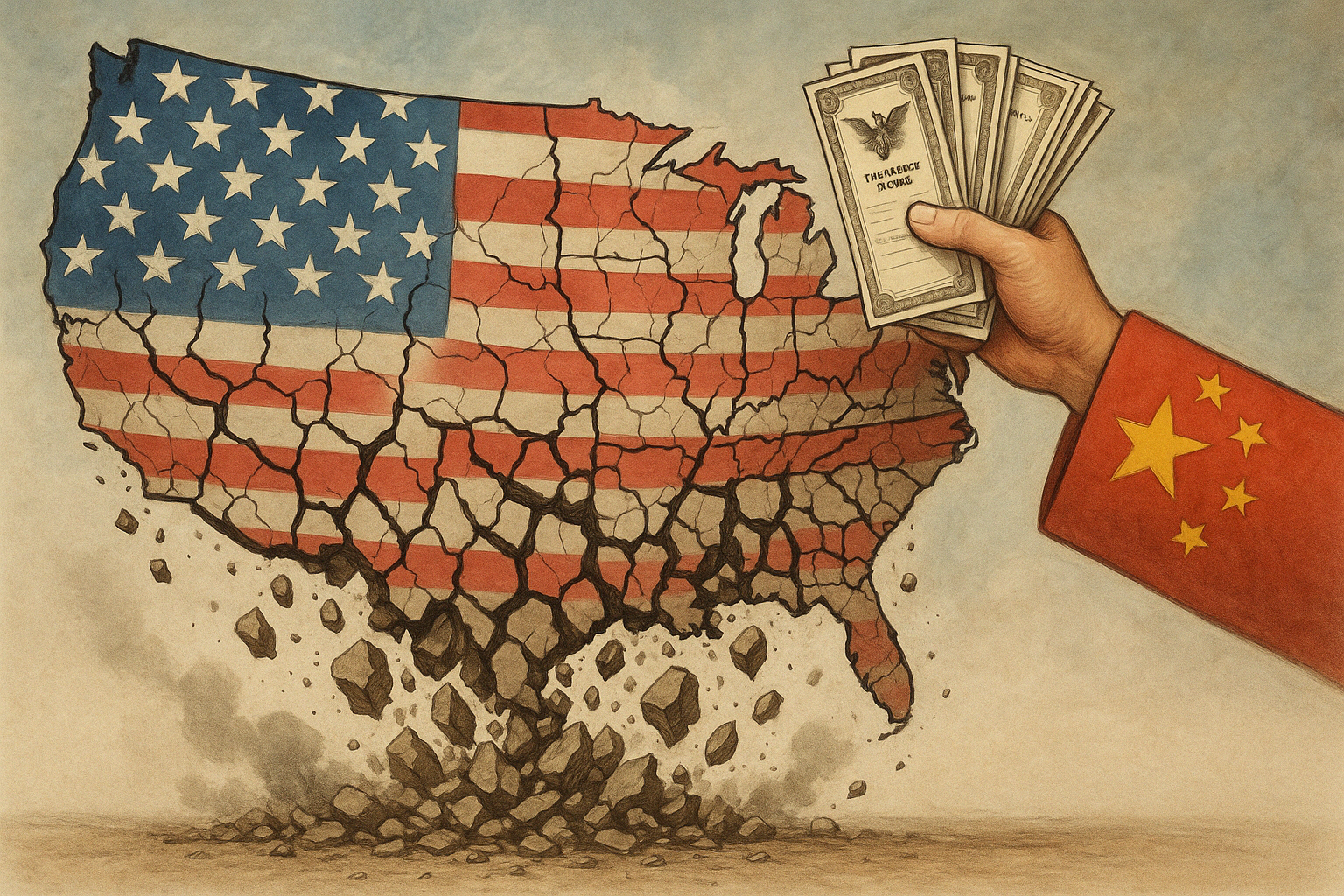

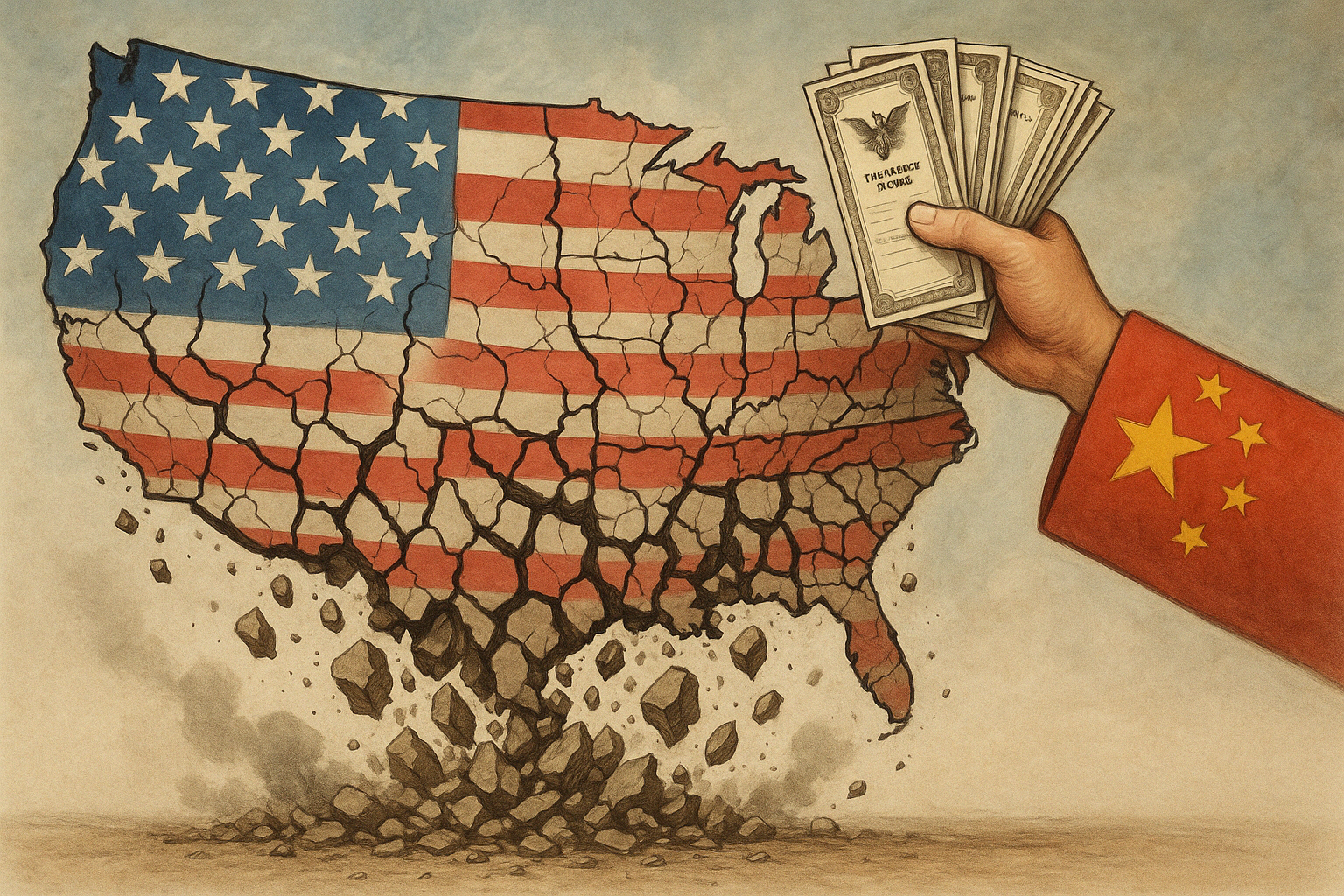

The world had stepped through a threshold. Diplomats still called for restraint, and editors still published op eds demanding dialogue. But behind every placating sentence was the gnawing truth: the destruction of the global order by the US a couple of years before resulted, not only in years of economic pain for common Americans and the rest of the world, but in the other powers not trusting that the US was up to the game anymore.

And above them, high over the Pacific, Chinese satellites blinked awake.

Section Three: Echoes of Steel

Taipei, Taiwan, 10:22 AM (CST)

Yuan-Hao’s phone had already vibrated ten times before he answered it.

“Baba, they’ve locked our school down. We can’t even look outside the windows,” his daughter’s voice trembled through the line. “Are they really coming?”

Yuan-Hao Lin, thirty six years old, never wanted to return to uniform after his mandatory service. But he had. The past few years, he served in the reserves while working as a logistics engineer for a Taiwanese robotics firm. Yet this morning, everything else evaporated. The text came in at 05:46: Tier Two recall. Immediate reporting. No questions, no explanations. He had kissed his sleeping wife and daughter goodbye and slipped quietly into his uniform like it was 2015 again.

Now, in a reinforced command centre beneath a mountain in central Taiwan, he was staring at wall to wall screens tracking Chinese vessel movement. The map looked like it was bleeding red.

“Twenty four destroyers confirmed,” a lieutenant said behind him. “Submarines unknown. Airspace activity up seventy percent. We’re being painted every six minutes.”

“Civilians?” Yuan-Hao asked.

“Mostly calm. Power grid’s holding. But the news cycle is spinning. People want answers.”

He didn’t have them.

Outside, Taipei still hummed with life, markets open, scooters zigzagging through alleys, but it was a surreal calm, like a city waiting for an earthquake already registered on someone else’s Richter scale. No bombs had fallen. No invasions had begun. But the sense of impending fracture was everywhere. It sat behind every pair of narrowed eyes. In every extra bottle of water bought quietly at a corner shop. In the way shopkeepers glanced at the sky for no reason.

“Send our drone scouts out past Kinmen,” Yuan-Hao ordered quietly. “They need to know we’re not blind.”

And for a moment, as he stared at the creeping arcs of Chinese frigates converging in the Strait, he allowed himself to think the impossible: Maybe they aren’t bluffing this time.

Shenzhen, China, 11:55 AM (CST)

Captain Wu Lian sat aboard the Changsha, a Type 052D guided missile destroyer, slicing through the South China Sea like a blade through black silk.

“J20s crossing waypoint Echo,” his communications officer reported. “No resistance. Taiwanese jets just shadowing.”

Wu nodded without looking. The sea was calm. The operation, Joint Sword 27, had been rehearsed a dozen times under different names. Exercises. Simulations. But this was different. They were moving into a live corridor, where American satellites watched and enemy radar whispered back like ghosts.

And yet, the men weren’t tense. They were focused. Silent. Trained. They believed in the mission.

Wu, a fifty two years old veteran of China’s rapid military rise, had long kept his own counsel. He read Sun Tzu, but he reread Clausewitz. He knew politics sat at the end of the gun’s barrel, and he also knew how easily a gun could slip from one hand to another.

His orders were clear: move into a pre assigned grid, display naval presence, do not fire unless fired upon.

But he knew. Everyone knew. This wasn’t a rehearsal anymore. This was the shaping of a new epoch.

“Distance to Taiwan coast?” he asked softly.

“Seventy nautical miles.”

He stood, walked to the reinforced bridge window, and gazed out at the horizon. The sky shimmered, perfect and quiet. Almost deceitfully beautiful.

“We do not act first,” he reminded his officers. “But we do not hesitate.”

Behind his back, a young sailor murmured to another: “You think they’ll actually invade?”

Captain Wu didn’t answer. But he remembered the briefing the day before.

In twenty four hours, the West will blink.

New York City, 01:38 AM (EST)

Travis Berman hadn’t slept. Not since Tokyo’s Nikkei opened with a 900 point plunge.

Now he sat in the conference room of a mid-tier hedge fund in Lower Manhattan, sweating through his shirt as alerts pinged from his laptop like popcorn.

“This isn’t a selloff,” he snapped at the room. “It’s a damn exodus.”

“Travis, it’s military tension,” his boss, Andrea, said, trying to keep calm. “They haven’t fired a shot. It’s just fear. People will hedge back in when the smoke clears.”

But Travis wasn’t buying it. Not this time.

His screen showed the Hang Seng dropping 11%. Semiconductor indexes were cratering. Taipei’s stock exchange had halted twice already. The VIX, the volatility index, was spiking like a heart monitor in cardiac arrest. And the yuan was holding steady, unnaturally steady.

“That’s the part I don’t like,” he muttered. “Everything else is chaos. But the yuan’s anchored. It’s not supposed to be.”

No one responded. They were too busy staring at the red waterfall pouring down their Bloomberg feeds.

Outside, New York was still asleep, but already whispers moved through elite circles. “Taiwan.” “China.” “Could this really be it?”

Travis checked the time. In two hours, the pre-market would open. He sent an emergency note to his clients: Consider rotating out of East Asian equities until further notice. Hedge against Pacific exposure. Stay liquid.

He stared at the bolded sentence. Then deleted “until further notice.” Replaced it with: Indefinitely.

Taoyuan, Taiwan – 12:03 PM (CST)

Hsu Meiling adjusted the straps on her five year old son’s backpack while glancing nervously at the apartment television.

“Military drills,” the anchor was saying. “We repeat, these are military drills. There is no invasion.”

Her husband, Zhen, a civil engineer, came in from the balcony, where he’d been trying to get reception on his phone.

“I think we should take the car. Go inland. Just for the day.”

Meiling nodded. Her hands trembled as she zipped her son’s jacket. He looked up at her, not afraid, just confused.

“Are we going on vacation?” he asked.

She smiled, a small, brittle thing. “Yes, sweetheart. A little holiday.”

But as she looked out the window toward the distant coast, where the sky was just a little too empty, a little too blue, she felt it. The pause before history stirs. The weightless moment before the avalanche starts to fall.

And then her phone buzzed, an alert from the government: Prepare emergency kit. Stay informed. Avoid coastal areas. Do not panic.

Meiling didn’t scream. She didn’t cry. She packed rice, bottled water, and batteries. She grabbed birth certificates. She kissed her husband tightly. She knew what was coming, not the details, not the headlines, but the feeling. The tectonic rumble of a world beginning to split.

Section Four: The Flight to Safety

New York City, 03:07 AM (EST)

Travis had seen panics before. Not like 2008, he was still in college then, but enough mini crises to know what market fear should look like. This wasn’t that. This was colder. Cleaner. Less frenzy, more algorithm.

“We’re seeing a full flight to safety,” his assistant barked, reading off the trader chat. “Oil just hit $147. Spot gold is pushing two thousand. And Bitcoin’s dipping to unassailable lows.”

“Of course it is,” Travis muttered. “Because why not?”

He toggled between tickers. The Dow Futures were down over 800 points. Taiwan Semiconductor, the most valuable chipmaker on earth, had lost 18% in four hours of Asian trading. In after-hours trading in the U.S., Nvidia and AMD were haemorrhaging value. The tech sector as a whole was buckling.

But what really worried Travis wasn’t the drop. It was how fast capital was fleeing.

“This isn’t just Taiwan exposure,” he said aloud. “This is global recalibration. They’re pricing in more than a standoff.”

Andrea walked in again, coffee in one hand, tie askew, trying to stay above water.

“They haven’t even fired a shot, Travis,” she said. “No one’s sunk anything. Not a single plane downed. It’s bluster.”

“Markets don’t care. Markets read fear like tea leaves. And every goddamn leaf says: this isn’t a bluff.”

A red notification slid onto his screen: WTI Crude crosses $150/barrel.

“Jesus,” someone whispered behind him. Then silence. Not one person in the office, not the veterans of Brexit, not the crypto maniacs, not the macro guys, had seen oil spike that fast since the first Gulf War.

“It’s gonna choke supply chains,” Travis said, half to himself. “Shipping rates, fuel, air freight. All of it. That’ll hit inflation again. Fed won’t know what to do.”

“And gold?” Andrea asked.

“Up 6% since midnight. Everyone’s running to it like it’s 1941.”

The tension in the room was thicker now. The market wasn’t panicking because it thought missiles would fall. It was panicking because it no longer trusted that they wouldn’t.

Berlin, 10:18 AM (CET)

Klara Eisenberg, deputy director of risk assessment at the Bundesbank, stood at the edge of a small operations room normally used for cyber drills. But this morning, it was repurposed for something more primal.

On the main display: collapsing indices from Seoul, Tokyo, Taipei, and now Frankfurt, the DAX down nearly 5% in the opening hour. German industrials, so dependent on Chinese contracts, were being hit like dominoes. BMW, Siemens, BASF, all bleeding.

She sipped cold coffee and scrolled through ECB updates. The bond yields across the eurozone were oscillating in ways that made no fundamental sense.

“This is all reflex,” she said. “No one knows what to price in yet.”

“The Asian markets will drag everything down,” her analyst said. “Everyone’s trying to rotate out of equities. But there’s no clear safe asset.”

“They’re buying oil and gold like mad,” she said. “Everything else is tainted by risk. Even treasuries are shaky.”

“Why?”

Klara stared at him for a long second.

“I don’t know,” she admitted. “I don’t like that I don’t know.”

Tokyo, 06:26 PM (JST)

The Nikkei had closed 11% down. The worst single-day performance since the Fukushima disaster.

Inside the Ministry of Finance, Deputy Minister Shinobu Mori ran a trembling hand through her silver-streaked hair. She had been in office for twelve years, seen enough currency crises and political eruptions to know when something was truly novel.

“This isn’t just a confidence problem,” she told the room. “Investors are seeing this as systemic. Structural. They’re thinking: if Taiwan is hit, how much of the global economy survives intact?”

One of her aides added, “The yen’s spiking against the dollar. Speculative movement.”

“Speculation is reality now,” she replied. “We need to hold the line, not let this become a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

But no one in the room really believed it could be stopped.

From the window, she could see the lights of Tokyo Bay. Ships were still moving. Planes still taking off. But the city felt fragile now, as if a hairline fracture had appeared somewhere no one could quite locate.

Taipei, 02:11 PM (CST)

Meiling and Zhen had made it inland by now, a town near the central mountains, where things felt quieter. But the tension followed them.

They sat in a relative’s home watching news cycles loop the same grainy videos: Chinese destroyers on the water, jets streaking above offshore islands, the President of the United States holding a press conference with strong reassurances and bellicose tones.

The local market was still open, but stripped of bottled water and canned goods. Rumours ran through the town like wildfire, that Chinese drones had landed, that the Americans were preparing to evacuate consulates, that missile systems were already targeting critical infrastructure, and that the US was mobilising its entire Pacific fleet towards Taiwan.

None of it was confirmed. But Meiling could feel the edges of society beginning to peel, not in chaos, not yet, but in the way people moved: faster, sharper, quieter.

Their son was watching cartoons. Blissfully unaware. Zhen turned the volume down and looked at her.

“If they come,” he said, “it won’t look like the last time. We’ll have no warning.”

Meiling nodded. Her hands were still trembling, just barely.

“I think they’ve already come,” she said. “Just not the way we expected.”

Section Five: The Ghost in the Flow

New York City, 04:42 AM (EST)

The sun still hadn’t risen over the East River, but Travis Berman’s third coffee was already half gone. The screens around him glowed like stained glass windows in a church of fear. After the US reassurance that it would defend Taiwan with all its almighty power, everything was red, not just Asian markets anymore, but Europe, the S&P futures, even utilities and healthcare. Defensive sectors weren’t defending. The “safe zones” were crumbling.

Still, there were no missiles. No sinking ships. No downed aircraft. Just manoeuvres. Just pressure and America rhetoric.

And then something small, almost nothing, blinked into his peripheral screen.

Bond Movement Alert, Singapore / Zurich, USTs (10Y), Volume spike.

He blinked, leaned forward, and checked the line item again. Ten-year U.S. Treasury bonds, one of the safest, most liquid assets on earth, had just seen a sudden, unusual sell side volume coming out of Singapore. Not huge. But weird. The kind of weird that traders are trained to notice.

Then Zurich. Another dump. $2.4 billion total between the two.

He frowned.

“Hey,” he said to one of the analysts, “check the offshore bond flows. T-notes. Use our Asia Pacific overlays. See if anything’s coming out of China linked accounts.”

“Why would they be selling Treasuries now?” the analyst replied, incredulous. “That’s suicide.”

“I didn’t say they were. I said check.”

Travis turned back to his screen, mind ticking faster now. The markets were melting down, but that alone didn’t explain Treasury movement. Normally, in a geopolitical crisis like this, U.S. government bonds surged in demand. Investors fled to them like lifeboats in a storm. Yields should’ve been dropping. Instead, they were ticking up. Not wildly, but enough to be wrong.

Something didn’t fit.

He opened a private Bloomberg terminal and began digging. Twenty minutes later, he had three more anomalies. All small. All within offshore jurisdictions tied to Chinese banks or intermediary institutions often used for sovereign activity.

Not enough to confirm anything. But enough to feel it.

He leaned back and exhaled. A ghost was moving through the system.

And that’s when the old argument came screaming back into his brain, the one every economist, analyst, and politician had agreed on for decades: China would never sell its Treasuries.

It had been the backbone of the unspoken détente between the world’s two largest economies, Mutual Financial Destruction. China was the largest foreign holder of U.S. debt, with over $800 billion in Treasury securities. More, if you counted shadow accounts and sovereign proxies. Selling those en masse would tank the dollar, spike U.S. interest rates, cripple the very demand China needed to maintain its export driven economy. It was financial seppuku, using its Japanese neighbours word.

And so, the assumption had calcified into gospel: China won’t dump U.S. Treasuries. They can’t afford to.

Every major policy paper said the same. Every central banker echoed the refrain. Even during the 2025 trade war, Beijing had never weaponized its holdings; it was Japan that started selling theirs causing the US to backtrack partially on their destruction of the order they have created for their benefit. The logic was airtight.

Except Travis had always hated airtight logic.

He knew markets. And markets, especially in times of crisis, weren’t driven by reason. They were driven by fear, and sometimes, by purpose. Strategic purpose.

He opened another screen. Pulled up data going back ten years. Looked at China’s slow, steady reduction in UST holdings since 2013. Nothing drastic. But patient. Almost…methodical.

“Hey Andrea,” he called across the floor, voice quieter now, “you remember what everyone said during the last trade war? About the nuclear option?”

She looked up from her own mountain of chaos. “Yeah, that China would never nuke the bond market.”

“Right. Because it would destroy their own reserves, make their existing portfolio worth less, spike their borrowing costs.”

“And cripple their economy,” she added. “It’s been the assumption since 2001.”

Travis didn’t respond. Just stared at the numbers. Tick by tick.

“What?” she finally asked.

“I think they’ve found a way around it.”

She narrowed her eyes. “What do you mean?”

He turned the screen so she could see. Showed her the volume spikes. The seller profiles. The jurisdictions. The creeping uptick in yield on bonds that should’ve been gaining.

“I think,” he said slowly, “they’ve been preparing for this for years. Hedging quietly. Building buffers. Gold, euros, yuan reserves. Every time they bought Treasuries… I think they were covering the loss ahead of time.”

Andrea looked at the screen. Back at him. Then leaned in.

“If that’s true,” she said, “we’re not just dealing with a military feint.”

“No,” Travis said. “We’re in the opening moves of a coordinated economic war.”

He exhaled again. The office around them hummed with nervous motion. Screens flashing, analysts whispering, someone crying quietly near the coffee machine.

“Still early,” he muttered. “Still just tremors. But if they’re really pulling the trigger…”

He didn’t finish the sentence. Didn’t need to.

Because everyone knew what came after the tremors.

Section Six: The Quiet Realization

Washington, D.C. 06:23 AM (EST)

The conference room on the second floor of the Eisenhower Executive Office Building, adjacent to the West Wing, had the unmistakable energy of a room just behind the frontline of history. Not chaos, not yet, but the kind of taut alertness that made people speak with half breaths and blink too often.

No one wanted to be the first to say it.

Deputy Secretary of the Treasury Rachel Kaminsky stared at the Bloomberg dashboard that had been pulled up on the wall screen. The data was granular, broken down by market hours, jurisdictions, trading volume. Quiet. Too quiet. Except for a few disturbing outliers.

“Zurich and Singapore,” her analyst said, tapping his pen against the chart. “Volume anomalies. $6.1 billion in total so far. All in 10 year and 30 year T-bonds. No short term instruments.”

“No sales from domestic U.S. accounts?” Rachel asked.

“Not yet. But European funds are starting to move cautiously, not dumping, just rotating into cash.”

“And the Chinese angle?”

He hesitated. “We don’t have direct attribution. But… two of the firms involved are known proxies. Remember the ones we flagged back in ’21 for indirect Belt and Road financing?”

Rachel leaned back in her chair, lips tightening.

“It’s too early,” someone else said. “Too little volume. It could be pre-emptive hedging by funds exposed to Taiwan risk.”

Rachel didn’t respond. She was remembering a meeting from six years earlier, in an IMF backroom, when a Chinese delegate had casually said: “Every financial empire thinks it’s too big to be unplugged. You only realize it when the power goes out.”

She turned to the NSA liaison sitting in the back corner. “Are we seeing any cyber spikes in financial infrastructure?”

He nodded, flipping open a tablet. “No penetration. But there’s increased traffic, coordinated, patterned, clean. Recon level pings on Fedwire, SWIFT relays, and secondary liquidity hubs.”

“So,” Rachel said, fingers interlaced tightly, “they’re looking at the plumbing.”

London,11:34 AM (GMT)

In a fortified wing of the Bank of England, Charlotte Parris, Director of Global Risk Surveillance, wasn’t watching the pound. She wasn’t even watching the FTSE anymore. She was watching yields.

“Look at the curve,” she said to her deputy. “Ten-year moving up faster than the thirty. No safe haven behaviour. This is a targeted move.”

The younger analyst frowned. “Everyone’s saying it’s market noise. Military nerves.”

“This isn’t nerves,” she replied. “This is institutional. Intentional.”

She pulled up the historic spread curve between Treasuries and Bunds. The differential had narrowed overnight, not by much, but by enough to catch her eye.

“Someone’s forcing a revaluation of dollar trust,” she murmured. “Not selling off in panic. Trading out.”

Then, more softly: “This is what it looks like when someone tries to unwind a financial empire without making a sound.”

Frankfurt – 12:09 PM (CET)

The ECB’s Market Stability Council had been in session for four hours. They were supposed to break for lunch thirty minutes ago, but no one moved.

A German analyst with a thick Bavarian accent was presenting a breakdown of unusual gold transactions over the past eighteen months. “We believe these purchases were masked by intermediaries in non-reporting jurisdictions, but the origin trails back to Chinese-controlled entities.”

One of the French delegates leaned forward. “So they’ve been preparing for dollar turbulence?”

“Not preparing,” the analyst corrected. “Designing.”

The room went still.

They weren’t just witnessing a market crisis. They were watching the early contours of an engineered global reordering , still deniable, still faint, but with a shape that could no longer be ignored.

Someone whispered, “Is this the financial decoupling we were warned about?”

A British voice near the door said grimly: “No. This is what decoupling looks like. We’re already in it.”

New York City – 07:03 AM (EST)

Travis sat alone now, headphones in, watching the Japanese yen hit 138.5 against the dollar. It was supposed to be a win for the greenback, but it wasn’t behaving like one. Liquidity was thinning. Bid ask spreads on high-volume Treasuries were widening, slightly, but measurably.

His screen pinged again.

BREAKING: South Korea’s KOSPI down 14%. Emergency circuit breaker activated.

He barely glanced at it. His attention was now locked on a new message from a contact at a Geneva-based clearing house.

“We’re seeing longer duration USTs being unwound. Multiple desks. Looks surgical. Some of these desks haven’t moved positions in years.”

He closed his eyes.

This was the moment before the moment.

The markets hadn’t screamed yet. But the people who knew how to listen, to the flow of capital, the rhythm of safe havens, the murmurs of liquidity, they were starting to hear something.

And that something was a strategy.

Not a panic. Not a reaction.

A plan.

And plans, when executed at this scale and if originated in Beijing, didn’t reverse course.

Section Seven: Shattered Assumptions

Washington, D.C., 08:19 AM (EST)

It hit like a slow avalanche.

At first, the Treasury Department believed the initial dump could be managed, isolated volume. A correction. A market spasm in reaction to Taiwan tension. They’d seen worse. But by mid-morning in New York, it was no longer a trickle.

It was a rupture.

The data feeds were clear. By 08:07, $26 billion in U.S. Treasuries had been offloaded through accounts in Singapore, Luxembourg, and Zurich. Another $9 billion appeared to be moving via Hong Kong intermediaries, cleverly disguised as corporate reallocations. In aggregate, it was massive. In form, it was disciplined. Not a panic. A program.

The ten-year yield had shot up past 5.1%, a 74-basis-point jump in under six hours. Repo markets began flashing yellow. Treasury dealers widened spreads again.

Inside the West Wing, the National Economic Council met with the Fed Chair, the Secretary of the Treasury, and the National Security Advisor. What was meant to be a closed-doors discussion became something closer to a crisis war room.

Rachel Kaminsky dropped the paper in front of the room.

“We’re looking at nearly $70 billion in Treasuries sold in the last nine hours.”

The Fed Chair shook his head. “This makes no sense. They’re nuking their own portfolio. If they keep this up, they’ll wipe out half the value of their remaining holdings.”

“And yet,” Rachel said flatly, “they’re still selling.”

“But why?” asked a political advisor, pacing. “Why would they do it? We’ve always said this was their insurance policy. That dumping Treasuries would hurt them more than us.”

The room went silent.

Then a voice from the back, a young economist on loan from the IMF, spoke up.

“What if that assumption was based on the wrong premise? What if… every time they bought Treasuries, they were also buying a way out?”

Heads turned.

He went on. “They’ve been quietly accumulating euros, yuan-denominated debt, and physical gold. Not in headline numbers, but in the shadows. Through sovereign funds, intermediary banks, strategic swaps. Every purchase of a Treasury bond was balanced with a hedge.”

“Meaning what?” the Fed Chair snapped.

“Meaning they’ve spent twenty years building an escape pod, so they could cripple the US economy without affecting theirs, impeding any response when they decided to invade Taiwan.”

London, 01:44 PM (GMT)

In Canary Wharf, the crisis room at the UK Treasury was buzzing. Analysts and economists pored over secondary market data, trying to track the source nodes of the cascade.

Charlotte Parris, at the Bank of England, connected in via secure line.

“It’s too clean,” she told them. “This isn’t capitulation. This is sequencing. A deliberate unwinding of long duration notes first. Followed by targeted middle range bonds.”

“And short term?” someone asked.

“Untouched, for now. Which tells me they’re timing it. They’re managing the optics, trying to keep the dump just below overt panic, yet, but well above strategic shock.”

One of the senior political officials, his voice half panicked, asked, “But why now? We’ve known about Taiwan tensions forever. They’ve never done this before. Why now?”

Charlotte responded without hesitation. “Because they have decided to take Taiwan and are making sure that neither the American nor us have the resources to stop them, all while finishing the demolition of the preexisting world order, as started by the US in 2025. And because they’ve built their reserves and the alternative networks to a point where the damage is now survivable.”

Another analyst added, “And if they can shift international settlements into gold or yuan, even temporarily, the sell-off becomes a tool, not a cost.”

“Are you saying they want a dollar crisis?”

“I’m saying they’ve spent twenty years preparing for one., one that ends the dollar reign for good”

Beijing, 09:08 PM (CST)

Inside a secure wing of the People’s Bank of China, the Deputy Governor watched a live Bloomberg feed showing a red waterfall of global bond market chaos. There was no celebration. No visible satisfaction. Only quiet calculation.

“We’re at $81 billion,” a finance aide reported. “Another $20 billion queued by midnight. Zurich and Dubai are fully operational. The gold floor is absorbing 70% of the liquidity shift. Yuan demand from Belt and Road accounts has tripled.”

“Any feedback from Moscow and Tokyo?” the Deputy Governor asked.

“The Russians are holding their dollar reserves for now. But ruble-yuan swaps are active and expanding. In Japan, they are not selling their bonds, but our alliance after the 2025 trade wars seems to stay solid”

The man nodded. The design was working. The foundation had been laid long ago.

China’s strategy wasn’t to destroy the dollar outright. That would be too fast, too chaotic. Instead, the goal was subtler, to prove, first, that the dollar was not untouchable. That it could be targeted. That it could bleed.

And in that bleeding, the remains of trust that were left after the US dynamited the system that it had created, would further erode.

Frankfurt , 02:11 PM (CET)

At the Bundesbank, Klara Eisenberg leaned forward, hands folded under her chin.

She’d just received word from a confidential source: the Swiss National Bank had begun quietly shifting some of its reserve mix out of dollar-denominated assets. Not yet a policy move, just “precautionary rebalancing.” But the message was clear.

Confidence was faltering.

“We’re approaching a monetary pivot point,” she said to the room. “Not because the dollar is crashing, but because people are realizing that it can be made to crash.”

A French economist near her said softly, “The idea of U.S. invincibility, it’s what’s been holding the system together. Once the idea breaks…”

“It doesn’t come back,” Klara finished.

New York City, 09:31 AM (EST)

Markets opened to chaos.

The Dow dropped 1,300 points in the first fifteen minutes. Trading halted on five major banks due to volatility. Gold hit $2,100. Oil cracked $158 per barrel. And the ten year Treasury yield was pushing 5.7%, a death knell for mortgage rates, for credit markets, for any future soft landing.

Travis sat at his desk, shoulders rigid, jaw tight.

“It’s happening,” he said aloud.

Andrea didn’t need to ask what “it” was.

Around them, traders yelled, phones rang, screens blinked like warning lights in a failing aircraft. But Travis felt oddly still. Almost frozen.

All those years of dismissing the threat. All those policy briefings, journal articles, academic panels, all grounded in the belief that China was too smart to cut off its own legs.

They weren’t cutting off anything.

They’d just built themselves a new pair.

Section Eight: Architects of the Quiet Sword

Beijing, 09:53 PM (CST)

People’s Bank of China, Inner Directorate Chamber

The room was cold, windowless, and silent. Phones were left outside. Devices turned off. There were no transcripts, no minutes, just memory, discipline, and old loyalties.

At the head of the table sat Luo Min, Deputy Governor of the People’s Bank and one of the principal architects of the operation codenamed Project Qingxuan, loosely translated: the Clarity After the Mist.

He was seventy one years old, silver haired, with the quiet demeanour of a professor more than a financier. For most of his career, Luo had been underestimated, too soft-spoken, too methodical. But in the cracks of the 2008 financial crisis, when the dollar buckled and the Fed printed its way out of the abyss, Luo had seen the future.

He had written it in a memo that only three people ever read:

“The empire is built on a promise of return. But if we reshape the conditions of belief, the promise fails.”

Now, fifteen years later, the reshaping was in motion.

“Zurich reports full transition from phase two to three,” said a younger man to Luo’s right, Qi Haoran, a strategist from the State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE). He was in his forties, fluent in German and Python, and had spent two years embedded in the IMF under a false identity. He’d written the original code that allowed the obfuscation of sovereign backed shell companies and layered financial positions across Singapore, Mauritius, and the Caribbean.

Luo nodded.

“Confirm gold buffer levels?” he asked.

“Over targeted by 11%. Physical delivery schedules intact. Dubai, Vladivostok, and Djibouti all reporting compliant storage volumes. No interruptions.”

“And the Belt and Road accounts?”

“Most of the African and Central Asian recipients have shifted to yuan-denominated settlement. Latin America is slower, but moving.”

A woman across the table, Gao Yini, Deputy Minister of Commerce and the bridge between the financial operation and the foreign policy apparatus, leaned forward. “The Americans are still clinging to the belief that this is emotional. A lashing out. They haven’t yet realized it’s a conclusion.”

Luo sipped tea, bitter, cooling.

“They have long assumed we are prisoners of their rules,” he said softly. “Because we used their currency, bought their bonds, followed their markets. They believed this meant dependency. But dependency only matters when there is no alternative.”

Gao nodded. “And now there is.”

Silence returned. On the wall behind them, a live feed ticker showed U.S. Treasury yields rising in slow but steady pulses, like an accelerating heartbeat.

Qi broke the quiet.

“There will be pain for us too. Exports will contract. Dollar based deals will be renegotiated. Our own real estate sector is still brittle.”

“Yes,” Luo said, “but pain is not collapse. And pain is survivable when prepared for.”

Gao added, “The Americans assumed their pain would always be our pain.”

Luo turned to her. “They forgot what it meant to plan for twenty years instead of for the next quarter.”

Ten Years Earlier , 2017, Hangzhou, An Unmarked Office on the West Lake

The first models were tested here, in a side building of the China Academy of Social Sciences. A small team of ten economists and mathematicians ran simulations under the direction of Luo Min, who was still then only a senior advisor to the PBoC.

They fed in datasets: China’s Treasury holdings, historical bond volatility, global reserve flows, oil prices, geopolitical events. Then they designed a game theoretic engine: How long could the US hold before having to stop all military operations due to the economic impact of a sudden Treasury bonds sell off? How long could China sell Treasuries, in various masked forms, before it triggered self-damaging blowback?

The results surprised even Luo. If done slowly, over decades, building gold reserves, shifting Belt and Road debts to yuan, locking in oil contracts outside the dollar, a day could come when the pain was bearable. And on that day, while even a partial dump of U.S. Treasuries would stop US military operations, a substantive sell off would not crash China’s economy.

It would wound it.

But it would mortally undermine trust in the U.S. financial system, and it would make it unable to fund a military operation like the one needed to defend Taiwan against a Chinese invasion.

The plan was born.

Back in 2027, Beijing, Now

Qi was reviewing updated sell numbers: another $14 billion queued. The pace had quickened. Not fast enough to collapse the markets, just fast enough to force doubt.

Gao handed Luo a document from the Ministry of State Security. Western intelligence agencies were just beginning to align the anomalies. Articles were leaking. Market strategists were starting to write the unthinkable: that China was dumping U.S. Treasuries, not reactively, but methodically. Deliberately.

“It will take them two weeks to say it aloud,” she said. “Three more to name it what it is: a financial offensive.”

“And by then?” Luo asked.

Qi smiled, almost sadly. “By then the psychology will have changed. The dollar will still stand, but not as a god. Just as a currency., and the US will not be able to rely in its fallen deity to keep its global military presence.”

Luo closed his eyes and leaned back.

It wasn’t vengeance.

It wasn’t chaos.

It was design.

Section Nine: The Sound of Surrender

Washington, D.C., 5 October 2027, 08:12 PM (EST)

White House, Situation Room

There were no raised voices anymore. No outrage. No pounding of tables. Just silence.

The room smelled faintly of coffee, sweat, and defeat.

The Chairman of the Joint Chiefs had just finished presenting a revised assessment. PLA forces had completed a full encirclement of Taiwan, a maritime and aerial quarantine more than a blockade. No military action had occurred. No missiles fired. No troops landed. But nothing could get in or out of the island without passing through the teeth of China’s military.

The President sat motionless, hands folded beneath his chin. He looked like someone attending a funeral he’d long feared. His childish discourse and attitudes did not serve against a rational, mature and calculating adversary.

“And there’s nothing they’ve done we can officially call an act of war to rally our allies?” he asked.

The Secretary of Defence shook his head. “Not by the book. They’re operating in international waters and airspace. Aggressive? Absolutely. But legal. Barely. And, what allies are we going to call? We told them only two years ago that they needed to take care of themselves. They kicked Russia out of Ukraine without us”.

“And the bond markets?”

Rachel Kaminsky, Treasury, gave a brief nod. “Yields are stabilizing, at high levels. $134 billion in USTs liquidated over four days, and they still hold more than $650 billion that they can sell. Gold continues to surge. The Fed has burned through $480 billion in emergency facilities just to restore liquidity. We’ve still got tools, but…” She paused. “Not for long.”

“And the dollar?”

“Dented. Very dented. International settlements in yuan have quadrupled since Monday. Smaller central banks are hedging out of dollars. We’re not going to lose reserve currency status overnight. But the illusion of untouchability is gone.”

The President didn’t speak for a while.

Finally: “So what you’re all telling me… is that we can’t defend Taiwan.”

No one answered.

Because everyone knew.

They couldn’t.

They couldn’t move a carrier group into the Strait, it would invite escalation and test a defence perimeter already sewn shut. They couldn’t issue economic sanctions, not when the global markets were already absorbing the shock of China’s decoupling manoeuvre. They couldn’t isolate China diplomatically, not when half the Global South was suddenly trading in yuan or receiving loans from newly leveraged gold-backed instruments.

China hadn’t attacked Taiwan. It had surrounded it, with steel, silence, and solvency, while the US had abandoned the world with twits, shouts and mounting debts. So it soon discovered that its arsenal, tanks, planes, broken treaties, and Treasury bonds, was not calibrated for this kind of war.

London, 6 October, 02:47 AM (GMT)

UK Foreign Office, Emergency Advisory Council

Foreign Secretary Robert Finch looked up from his notes.

“Well then,” he said flatly, “they’ve won.”

No one corrected him.

A German ambassador muttered, “They’ve changed the rules of engagement. And we didn’t realize until we were already playing.”

The French delegate, normally eloquent, simply stared at the map.

Taiwan was encircled. Its skies monitored, its ports frozen in fear of miscalculation. And yet, there was no formal declaration, no images of war, only drones, satellites, and economic rupture.

“But the people of Taiwan…?” someone asked quietly.

“What do we do?”

There was no answer. Because there was no policy tool left that didn’t carry the risk of planetary financial collapse or actual war with nobody being able to foot the bill.

Taipei, 6 October,11:19 AM (CST)

Yuan-Hao stood atop a concrete outpost in the central highlands, watching through binoculars as a contrail arced far overhead, one of dozens circling above the island like hawks. He hadn’t slept more than two hours in five days.

His radio crackled with updates, troop drills, electronic jamming, brief incursions.

But there were no bombs.

Just pressure. Relentless, silent pressure.

His daughter was back in the city now. Her school remained open, but she hadn’t left the building in three days. His wife texted him short, brave messages.

And he knew, deep in his chest, what was coming.

Not a war. Not an invasion.

A wearing down. A slow suffocation of options until Taiwan became not conquered, but irrelevant.

Beijing, 6 October,12:02 PM (CST)

Zhongnanhai Compound

Luo Min stood by the koi pond, an old place of reflection in the heart of power, a present from their Japanese counterparts.

A young party official approached him with a message from the Central Committee. Praise, gratitude, triumph. Luo accepted it politely, nodded, and waved the man away.

He looked up at the sky, pale with smog and history.

They had not fired a shot.

And yet, the outcome was complete.

The world still functioned, the internet was on, markets were trading, aircraft flew. But something deeper had shifted, irrevocably. The illusion of economic invincibility, of Western permanence , was gone.

Taiwan might resist. Its people were proud, intelligent, determined. But in the years to come, it would face the same silent war being waged now: diplomatic strangulation, economic redirection, global fatigue.

Time would do the rest.

Luo dropped a crumb into the pond. The koi surged forward, briefly, then calmed again.

New York City, 6 October, 10:37 PM (EST)

Travis Berman left the office early for the first time in six days. He didn’t even remember what day of the week it was anymore. Midtown was still lit, New York never really went dark, but it felt quieter now. The kind of quiet that happens after something’s cracked but hasn’t fallen yet.

People passed him in murmured conversations,“…Taiwan’s ports still shut…” “…gold hit $2,150…” “…China sold how much?” No one had answers. Just questions, headlines, half-wrapped theories. But Travis had stopped asking.

He stood still for a long moment. The lights of the city still buzzed outside. The world was still spinning. Markets would reopen. Statements would be made. Panels convened. Strategies adjusted.

They had not been outgunned.

They had been out thought.

He walked three blocks north, almost on instinct, and stopped in front of his apartment building. Instead of going in, he turned and walked another block, to a 24 hour bookstore he sometimes ducked into when the markets were too loud.

He stepped inside and made his way to the philosophy section. There, untouched in the dim yellow light of the late-night shop, was a familiar spine: The Art of War, Sun Tzu’s original, bound in black cloth with gold script. He pulled it from the shelf. He turned to a section he remembered from years ago, during a late night cram session at Queen Mary in London. Back when these ideas felt like intellectual games. Now they read like prophecy.

He found the line. Read it three times before whispering it aloud almost laughing:

“The supreme art of war is to subdue the enemy without fighting.”

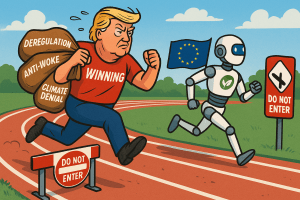

As Europe begins 2026, the continent finds itself at a crossroads in the governance of sustainability, technology and industry. Policymakers across the European Union and the United Kingdom are increasingly embracing deregulatory reforms, promoted as necessary to enhance competitiveness, stimulate investment and ease administrative burdens on business. Yet these reforms, when examined together, reveal a structural shift away from the sustainability frameworks that have shaped corporate accountability, environmental protection and long term innovation strategies over the past decade. This shift is more than a matter of regulatory calibration, reflecting a political economy in which deregulation is treated as an end rather than a means.

As Europe begins 2026, the continent finds itself at a crossroads in the governance of sustainability, technology and industry. Policymakers across the European Union and the United Kingdom are increasingly embracing deregulatory reforms, promoted as necessary to enhance competitiveness, stimulate investment and ease administrative burdens on business. Yet these reforms, when examined together, reveal a structural shift away from the sustainability frameworks that have shaped corporate accountability, environmental protection and long term innovation strategies over the past decade. This shift is more than a matter of regulatory calibration, reflecting a political economy in which deregulation is treated as an end rather than a means.