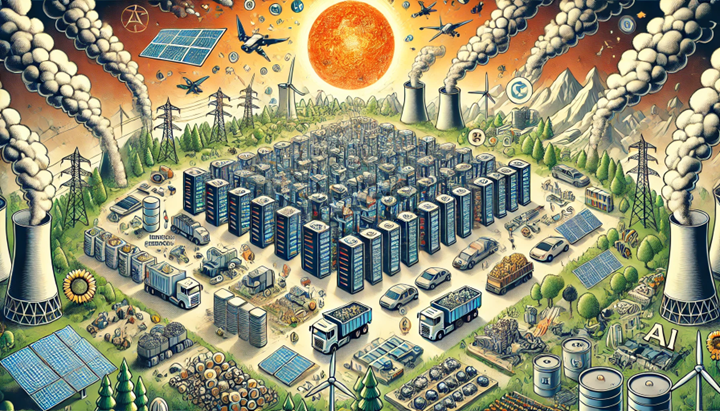

In the previous entry the issue of the environmental and climate change impact of AI use and development was presented as important, and in need of urgent treatment by policy makers (who are squarely ignoring it in most proposals of AI regulation). Those impacts are real, considerable and multifaceted, involving major energy consumption, resource depletion, and a variety of other ecological consequences.

Training large AI models requires immense computational power, leading to the use of large quantities of energy. Just as example, training a single model like GPT-3 can consume 1287 MWh of electricity, resulting in about 502 metric tons of CO2 emissions, which is comparable to the annual emissions of dozens of cars. But while the energy consumed during the training phase is significant, quite more energy is used during the inference phase, where models are deployed and used in real-world applications. There have been interesting forms to justify such a use, mainly by comparing pears not with apples but with scissors, but they seem to obviate the fact that the general human emission that are compared with the AI ones will be there regardless of the activity, so the improper use of AI adds emissions without subtracting much of them. In a world that the development and deployment of AI is bound to keep growing at bubble-like rates, this implies that the location of data centres plays a crucial role in determining the carbon footprint of AI, as they are bound to double their energy consumption by 2026 (if 170 pages is too much to read, simply go to page 8). Data centres powered by renewable energy sources, have a lower carbon footprint compared to those in regions reliant on fossil fuels, and there is an argument about making such use compulsory.

From the resource depletion and e-waste point of view, AI hardware, including GPUs and specialized chips, requires rare earth elements and other minerals. The extraction and processing of these materials can lead to environmental degradation and biodiversity loss. AI is been currently used to find ways to replace those rare earth elements, but even then, as AI technology evolves, older hardware becomes obsolete, contributing to a steep increase in the amount of electronic waste. Besides the global inequalities generated by the mountains of e-garbage currently dumped in developing countries, E-waste contains hazardous substances like lead, mercury, and cadmium, which can contaminate soil and water if not properly managed.

A less obvious but equally significant impact is water usage. Training AI models like requires abundant amounts of water for cooling data centres, with some studies claiming that the water consumed during the training of algorithmic models is equivalent to the water needed to produce hundreds of electric cars.

To add to the energy and resources consumption, the uncontrolled, improperly regulated widespread use of AI can have severe ecological impact, particularly and paradoxically, when used in activities where proper use of AI can minimize them. Not making sustainability a key aspect of algorithm design, training and AI deployment, may lead to situations that it is more profitable to carry on with environmentally harmful AI driven activities, like the overuse of pesticides and fertilizers, harming soil and water quality and reducing biodiversity, not mentioning that AI-based applications like delivery drones and autonomous vehicles can disrupt wildlife and natural ecosystems without giving much benefits (beyond increasing the already fat profits of few).

All this supports the idea that AI regulation must address sustainability issues and not leave to general environmental legislation, because it is important to know who owns what AI produces, but only if we have a planet where you can enjoy those works…

wow!! 54AI and environmental damage

LikeLike